Zero Escape: Virtue’s Last Reward

I’m not sure why they call Zero Escape: Virtue’s Last Reward the “spiritual successor” to the original 999: Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors game. The events of the previous game are spelled out for you during the course of Virtue’s Last Reward and referenced throughout the game, so we can just drop the whole “spiritual” thing and just call Virtue’s Last Reward the sequel to the original game — and it’s for this reason I highly, highly recommend playing though the original game for yourself before playing the sequel.

The first thing you have to know about Virtue’s Last Reward is that it’s the sequel to one of the best games I played this year, 999. This alone made it a must play for myself, seeing as I was this close to giving 999 the prestigious game of the year crown (stopped only by the fact it wasn’t released this year).

The second thing you have to know about Virtue’s Last Reward is that it is every bit as good as the original, which follows that if you enjoyed the original, then Virtue’s Last Reward will be right up your alley.

And that’s pretty much all you need to know about Virtue’s Last Reward; it’s a spiritual successor to one of the best games I’ve ever played, and it’s every bit as good as the original. Now, normally this is when I’d launch into my usual spiel of what the game is about, how you play the game, and just how damn good the game actually is (and why), and I’ll do that in just a second, but I also want to explore the characters themselves — there’s lots to say about each of the characters, and maybe it’ll mean a different review than you might normally read.

Virtue’s Last Reward is similar to the original 999. Very similar, in fact. They’re both story-driven games interspersed with puzzles/escape sequences, and they’re both better described as visual novels than typical games. They’re similar to The Walking Dead, in ways; there’s lots of dialogue, quite a number of cutscenes, and they’re both pretty light on actual gameplay.

But you shouldn’t shy away from either 999, Virtue’s Last Reward, or even The Walking Dead because of how story-driven they are. These three games are perhaps the most powerful games I’ve played, and all because of how damn good the stories they tell are — it’s like watching a movie, only because you have some part in how things play out, you feel all the more immersed. It’s an intense feeling you can’t get from reading a book, and it’s all the more real because you have some part in what happens.

There are quite a number of similarities between 999 and Virtue’s Last Reward. Both games prominently feature the number nine; nine main characters, a door with the number nine, and all with the number nine bearing a kind of symbolism that’s echoed throughout the game. Both games follow similar a gameplay style, too: novel sequences interspersed with escape sequences where you have to solve puzzles and find your way out of a room.

Like you did in 999, you’ll make choices in Virtue’s Last Reward that affect the story. In fact, Virtue’s Last Reward introduces a new gameplay mechanic that means there are even more possibilities than there were in 999. The introduction of the Ambidex Edition of the Nonary Game means you’ll be making more choices than ever before. There are stages of the game where you’ll choose to “ally” or “betray” your partner — without giving too much away, it’s this alliance or betrayal that determines how the game plays out.

It’s also this same alliance and betrayal game mechanic that also means that Virtue’s Last Reward is a slightly different game. 999 featured multiple endings, and Virtue’s Last Reward does as well: but in 999, the endings felt much more final. Besides the icons on the save screen, you weren’t really given any indication of how you were progressing towards the multiple endings, all to get to the one true ending. 999 made you play through the game in its entirety every time you wanted a different ending — I lost count of how many times I played through the first escape sequence, or how many times the characters were introduced to each other. Fast-forwarding dialogue was a welcome addition, but there was still a lot of extraneous gameplay.

Virtue’s Last Reward is different in that you’re given a “map” from the start that outlines all the possible paths the game can take. You have no idea how things will actually play out, but this map and your newfound ability to jump between different paths means you’ll spend a lot less time playing through parts of the game you’ve already played, as you can just jump straight to the point where you made a choice, make a different choice to the one you already made, and play a different path. It might sound confusing at first, but it makes perfect sense when you’re playing the game.

And that’s one of the best things about Virtue’s Last Reward: there’s a lot of complexity buried within the game itself, but it shouldn’t take you long to see through it all and see the truth. I know that might sound a little ho-hum, but it’s true: you might not realise what’s going on as you go about your business and solve puzzles, but it’s all there. All you have to do is play the game, and join the dots.

Certain endings in Virtue’s Last Reward won’t be revealed to you until you complete other endings. Of course, not every ending has these dependencies — but you’ll know when you reach those that do, because the game will end rather abruptly. At that point, it’s time to go play through a different path. Each path leads to a “good” ending, where you find out the true story behind one of the characters, and also a “bad” ending that’s not necessarily bad, but is one where you don’t get to find out any given character’s back-story.

Which brings us to the end of what I wanted to say about Virtue’s Last Reward. It’s similar to the original while being a little different, but it’s not so different as to be a radical departure from what made the original such a good game. As you play though the final path of Virtue’s Last Reward, you’ll realise that everything you’ve played through all makes sense — even if you have no idea why certain things happen at certain times.

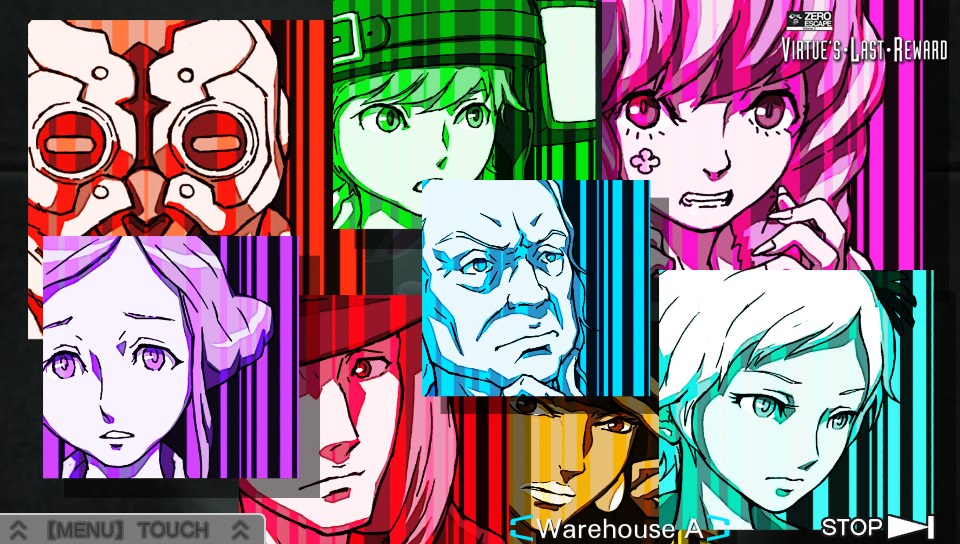

Now, to the characters. There aren’t any explicit spoilers as such, but I do give a few opinions based on my experience of the game. In no particular order…

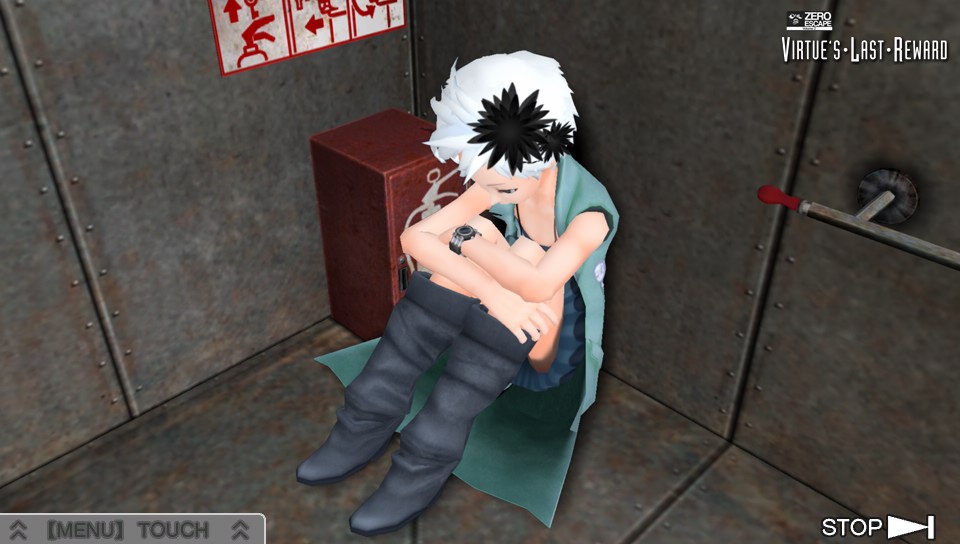

In Virtue’s Last Reward, you play the part of Sigma. You wake up in what you believe is an elevator, and from there, start on an amazing adventure. You’ll discover the true horror of your situation in due time, but for the most part, your goal is to find some answers to some burning questions. Why are you here, and for what purpose? And who are all these other people, and why are they here? What is the point of all of this? Your story is perhaps the most surprising of all — and undoubtedly the most complex. You’re the one solving puzzles. You’re the one searching for meaning. You’re the one playing though the different paths of the game.

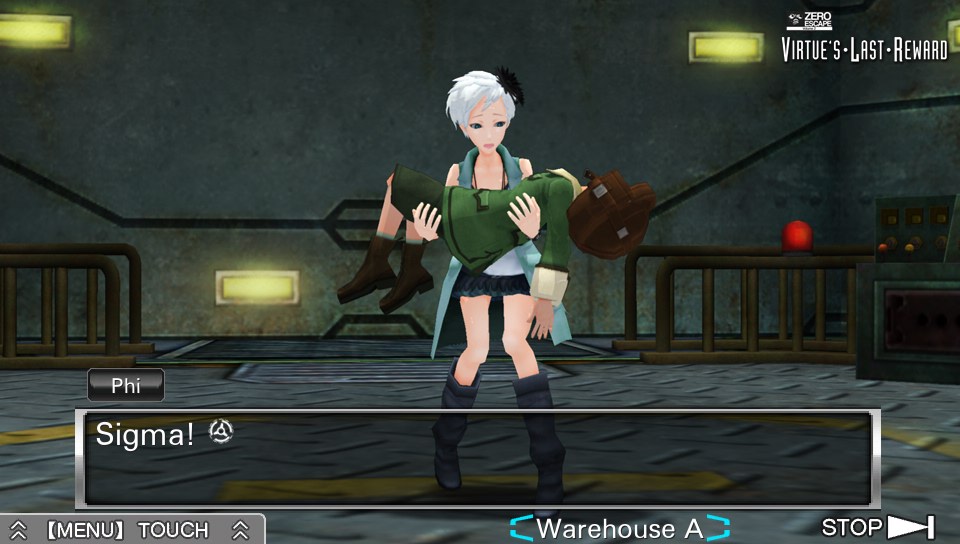

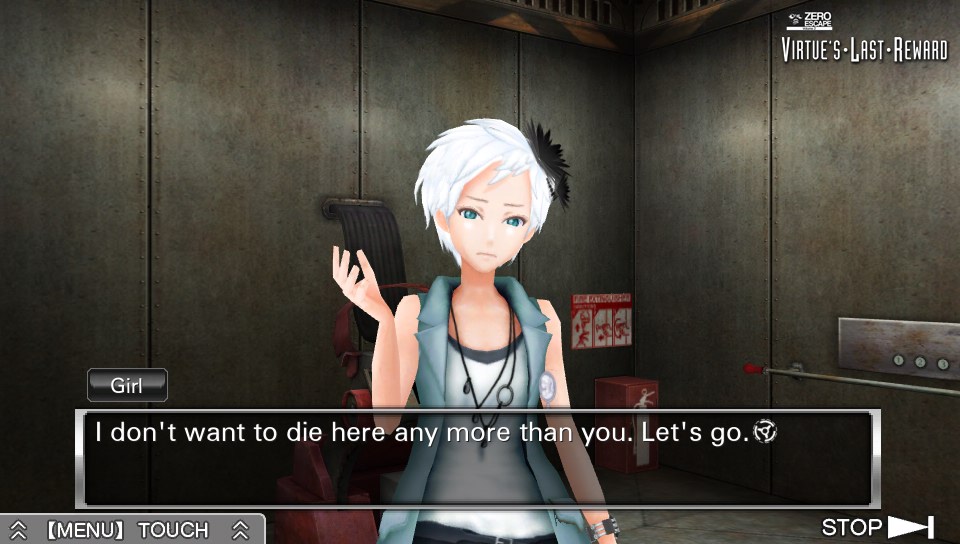

But when you wake up in the elevator, you’re not alone. A girl named Phi is here with you — you don’t know her, but she seems to know you. You have no idea how, of course. You feel a special bond between yourself and Phi — nothing that you can quantify or explain with words, but you just know that the two of you are… special, somehow. Chosen, perhaps. But for what? And by who? And perhaps most importantly, why? Phi has a few answers, but you’ll have to find out the rest on your own, or perhaps even with Phi. She might appear to be cold, but she’s smart where it counts. Her story isn’t revealed until the very end, but one thing’s for sure: she’s with you until the very end.

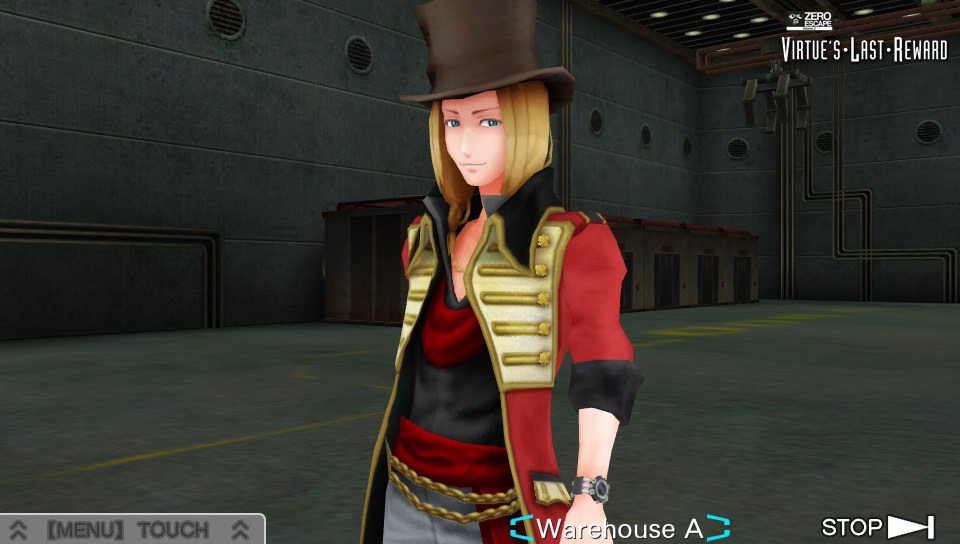

What can you say about a guy who’s dressed like he belongs in the circus? Dio is the kind of guy you’re not exactly sure about at first, but as you let events play out, you realise that Dio is actually a bit of a prick. And a selfish prick, at that — the only one he’s looking out for is himself, as evidenced multiple times throughout the course of the game. But what’s his deal? What’s he doing playing the Nonary Game like everyone else? Why does he act like a selfish, arrogant, stuck-up bastard? It isn’t until a little later on that you learn Dio’s true story, because he sure as hell doesn’t tell you the first time around, and perhaps not even the second. Dio is cast as the villain as the story from very early on, and maybe that’s closer to the actual truth than you know.

If you’ve played the original 999, you’ll already know Clover. She’s more or less the same girl you knew in the previous game, only a few years older. She seems to have some sort of relationship with another in the group this time around, too, but that’s about all you know at the start of the game. Similar questions surround Clover: why is she playing this Nonary Game? How come she already knows someone else in the group, and why are they here, together? Could her past experience with a Nonary Game have anything to do with it? If so, what?

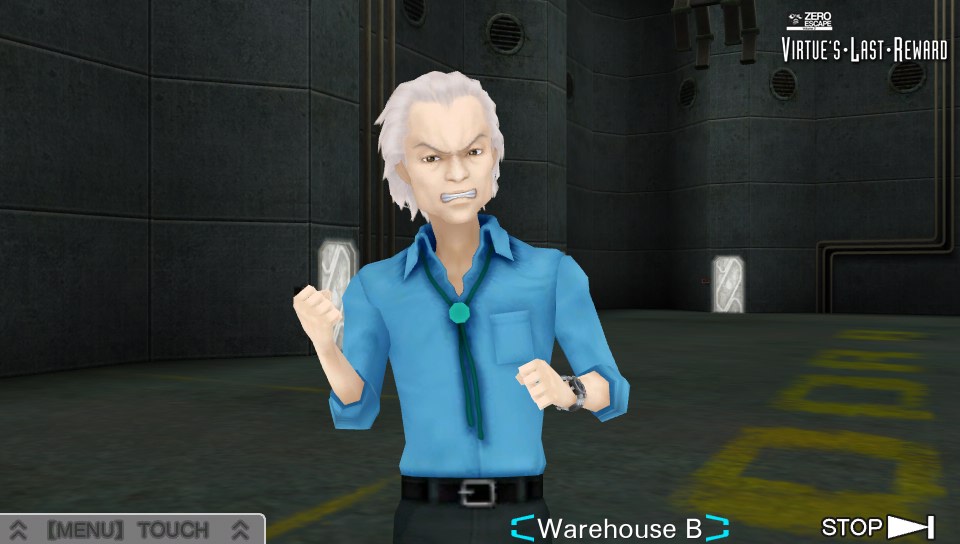

Somehow, it seems that everyone knows someone else in the group, and Tenmyouji is no different. He’s an old man who only wants to look out for his companion, who only wants the very best for him. If you take things at face value, it seems Tenmyouji doesn’t have any ulterior motives for playing the Nonary Game, but as you’ll discover during the course of the game, that’s where you’d be wrong. He’s on a quest of his own: searching for answers, maybe, but perhaps more accurately, searching for someone. But who?

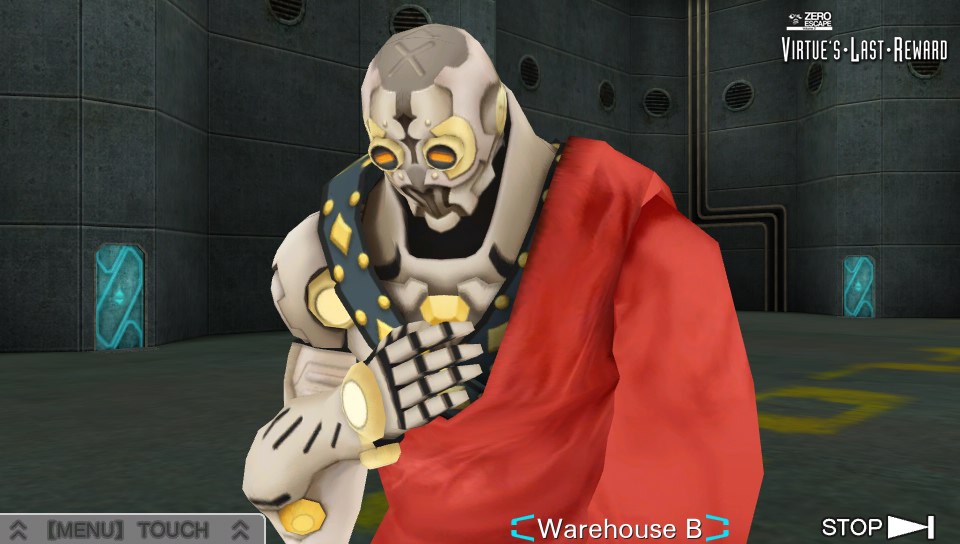

Very little is known about K, the man in a suit of armour, because he seems to be suffering from some kind of memory loss. And who asks pressing questions about a guy that’s wearing a suit of armour? He doesn’t remember putting on the suit of armour, but then again, he doesn’t remember his own name, how he came to play the Nonary Game, or anything else, for that matter. At first, you chalk K up to a mystery — you’re not exactly sure what is going on here, but you’re damn sure it can’t be anything good. Maybe there’s nothing sinister going on here, but maybe there is. Like many other aspects of Virtue’s Last Reward, you have too many questions, and not enough answers.

Alice and Clover seem to know each other, somehow, but this lady that looks more like some kind of exotic Egyptian princess is more than meets the eye. It isn’t until you hear it from Alice herself that you really find out what her story is. There’s no real mystery here, but Alice does fit nicely into the Nonary Game puzzle — and by that, I mean she has one specific part to play in this Nonary Game, an aspect so crucial to the rest of the game her survival is of the utmost importance. Clover comes as part of the package because of her previous experience, but it all seems a little too convenient, if you ask me. It’s like she’s as curious as you are when it comes to finding out the true purpose of this Nonary Game, but she also plays her role during other parts of the game.

For whatever reason, Quark is the one that Tenmyouji wants to protect above all else. I mean, he’s just a kid — how did he get mixed up in this Nonary Game business? With Quark’s young age also comes a sense of innocence — he’s done nothing wrong, has no real idea of what’s going on, but one thing’s for sure: he and Tenmyouji have a very special bond, and he trusts Tenmyouji all the way. Quark’s story is quite innocent, really — he’s only caught up in this mess because Tenmyouji is.

At first glance, you might assume Luna is just someone else that’s part of the game. But then you start to realise things, like how she doesn’t seem to be connected to anyone else — everyone else is connected in some way (Phi knows your name, Tenmyouji and Quark might even be related, Alive and Clover know each other too), even though you’re not sure about K (who isn’t even sure of himself). Or how she seems a little weird — maybe it’s how she always wants to please everyone. You can’t help but feel suspicious about someone who just wants to please everyone. She seems to have no real opinion of her own beyond wanting what everyone else wants — what’s up with that?

The end of Virtue’s Last Reward is, unquestionably, one of the most convoluted and complex conclusions I’ve ever come across, in any video game, ever. One of the things that made 999 great was the way it constantly built suspense all the way to the end — as you played through various endings, you learnt a little more about the Nonary Game and what you were all doing on board a ship in the middle of nowhere. Virtue’s Last Reward is like that as well — there’s hints and clues built into everything, but sometimes, all it takes for you to realise the truth behind everything is character spelling it out for you. You’ll uncover mystery after mystery, but there’s no time to dwell on things as the game constantly pushes you forward. To a better ending, perhaps, but certainly one which has a few more answers and a few more questions, to even things up.

Virtue’s Last Reward messes with you. It shocks. It awes. It leaves you wanting more. It’s an amazing, amazing game that leaves you guessing, right until the very, last, cutscene.

And that’s why I love it.

Footnotes: I played Virtue’s Last Reward on the PS Vita, where the touchscreen controls work well enough. By comparison, the 3DS version of the game has dual touch screens which would come in handy during the latter half of the game, but it’s more or less the same experience whichever platform you play it on. The copy I bought from the US PlayStation Network comes with both English and Japanese audio — you can play it in English if you want, but I find the Japanese audio adds a little extra to the game.