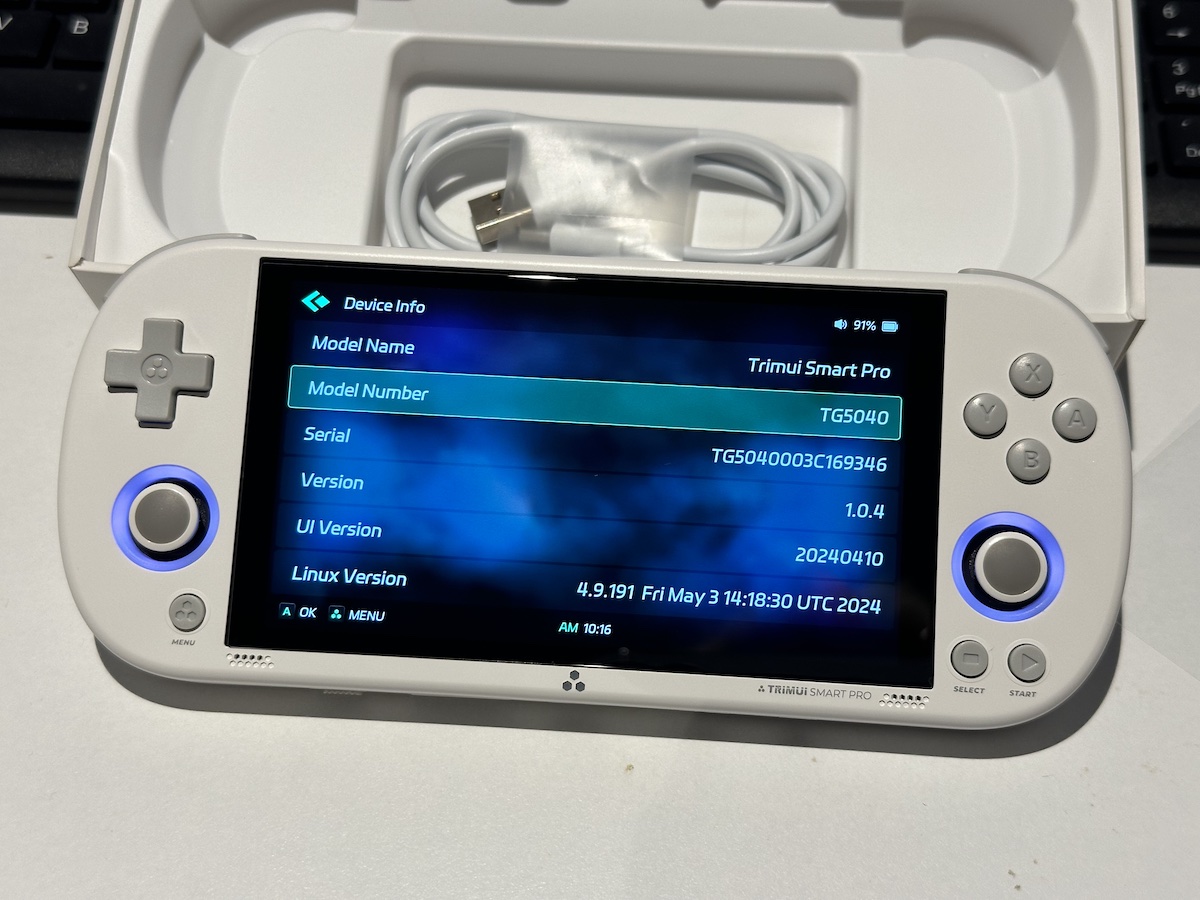

The TrimUI Smart Pro handheld console.

Basically a perfect modern GBA/DS emulator. It can run N64 and PSP, but I wouldn’t recommend it.

Every couple of years, I’ll go on a handheld gaming bender where I eschew all responsibilities and spend as much time as possible with my head buried in a handheld console, playing a game that might have been released 20 years ago. For those couple of weeks, I’ll be a teenager again, on holidays and having nothing to do but play video games on a handheld.

By any measure, we’re long overdue for one of those times. While Covid and lockdowns might have been the ideal time to dust off one or more of my old handhelds, I think I was more concerned about surviving and avoiding Covid than I was with playing a handheld console.

One of the great things about handheld gaming consoles like the 3DS and Vita — and indeed, all consoles — is that you can expect them to work 100% reliably with every game that was released for them, because that’s just how consoles work. There’s no performance issues. No incompatibilities. If you have a copy of the game and a working console, they you can always expect to play it, whether that’s 20 years ago when the console was first released, now, or 20 years from now. I know that I’ll be able to pull out my 3DS or Vita, give it a charge, and be able to pick up right where I left off. And that’s the beauty of consoles; they just work.

But as much as I love the Game Boy Color that I grew up with, the Game Boy Advance SP I eventually received, and the Nintendo DS that ended up rounding out the handhelds of my youth, I know this isn’t sustainable indefinitely.

The main problem with the handhelds that I have is that they, like me, aren’t getting any younger. The battery it has now is likely the best battery it’s ever going to have, and while 3D scanning and printing has come a long way and you’ll probably be able to buy replacement plastic parts, that’s not necessarily guaranteed for anything else including screens or other electronics. They’re not making any new 3DSes or Vitas, so there’s no way to get a new one unless I’m willing to pay a premium for one on the second hand market. Which means it’s a one way street for these handhelds, unless I get lucky and find a good second hand model for a non-exorbitant price. So as much as I want to be able to play all my Vita games on my Vita, or play all my 3DS games on my 3DS, I know that one day, that isn’t going to be possible due to time marching ever forward. Parts will break. Batteries will wear out. And when that happens, there’s no guarantee I’ll be able to restore them to working condition. Even if I can guarantee access to games that I want to play, which in 2024 and the age of digital downloads is absolutely not a given seeing as Nintendo has already shut down the 3DS eShop and Sony was about to do the same thing with the Vita PlayStation Store until they received backlash and reneged, there’s no guarantee that the hardware is going to last. How many consoles from 20 years ago do you know of, much less working examples?

Obviously this isn’t an option for even older handhelds like the GBA; in those cases the ageing hardware is even more of a limitation, and getting worse and worse every day. So for the purposes of gaming on a retro handheld like the GBC, GBA, or even a DS, then emulation is really the best option, with all of the inherent advantages and disadvantages that brings.

The question is whether I’m willing to live with the tradeoffs of imperfect software emulation for the conveniences of modern hardware and software. Modern hardware in this case is things like hall-effect analog sticks and triggers, USB-C charging, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and displays with such contemporary technologies like IPS (or ideally OLED, like the Vita had all the way back in 2012) and actual pixel density far above the handful of pixels that older consoles used to have. I’ve been PC gaming at 4K since 2015 at a healthy, if not incredible, 163ppi, so going back to anything less than 720p on a 5 inch display (293ppi) seems like such a huge step backwards when you consider that even the very first Apple Watch had 326ppi in 2015. Which, I’ll remind you, was almost ten years ago.

Modern software, on the other hand, means I can use software to emulate whatever console I’m interested in, provided my device has enough power to run those games. Whether that’s an Android or Linux-based handheld, or something like the PC-based Steam Deck, mostly depends on what I’m interested in playing given the hardware is more or less the same. Android, for example, currently doesn’t have emulators for Wii U, PS3, Xbox, or Xbox 360, and while that might change in the future, that’s the way it is right now.

Conceptually, I think I’m OK with having a device that doesn’t run everything. I think it would be weird to play GBA games on 6 or 7 inch screen, for example, irrespective of how good the integer scaling is, but I think a device that runs GBC, GBA, and even DS games could work. Then if I wanted to, I’d either have 3DS games on my 3DS, Vita games on my Vita, and potentially have another device for 3DS, Vita, and every other 8th-generation console, including GameCube, PS2, and maybe even Switch. From a hardware console perspective, this sort of separation works great as well because retro handheld consoles fit into one of a handful of tiers of modern hardware, each with varying power and price to handle its own set of retro handhelds.